Overview of concepts

Jobs and Tasks

A job is the entirety of the work to be performed. A job consists of multiple tasks, usually corresponding to a partition/shard of the data. For example, if your sharded DB has 100,000 shards, your job will have 100k tasks, one per shard.

Bistro takes the Cartesian product of the known jobs and the known shards (aka nodes), so specifying 7 jobs plus a database with 100k shards will result in 700k tasks for Bistro to execute. A job can set filters to reduce the number of tasks that it can run.

You write your own task — this is usually just a command + arguments to start on a worker machine, but you can also implement “a task is a service call”.

Bistro maintains the list of data shards, and executes the task against them in parallel, subject to resource constraints.

Resource Model

This is a brief summary of Nodes and Resources. You will want to read the full guide while setting up your Bistro deployment.

Bistro models data resources hierarchically, usually as a tree, though other structures are possible. For example: the children of a database host are the databases it serves, an HBase host contains regions, a Hive table splits into partitions, which in turn consists of files.

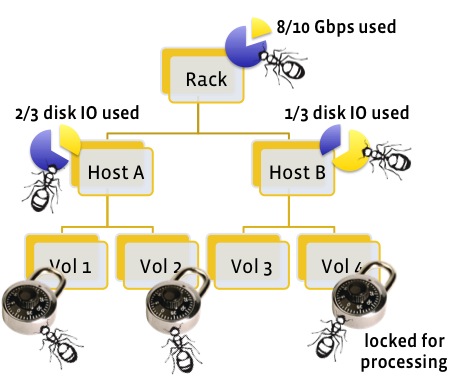

A three-level node tree, with resource constraints on:

- Rack switch bandwidth at the top (capacity of 10 Gbps),

- Host IO capacity in the middle (3 logical units available per host),

- Data volume-level locks with a capacity of 1 per volume.

A resource at each level is just an arbitrary label, such as “volume_lock” or “host_io”. Along with this label is a corresponding limit for how much of that resource is available at each node of the level.

Jobs specify the number of slots they consume from each resource in the job’s settings via resources → RESOURCE_NAME. If that is omitted, jobs use the default from bistro_settings → resources → LEVEL_NAME → RESOURCE_NAME → default.

Tasks run at leaf nodes in parallel if their resource requirements along paths to root are satisfied. For example, a task in the cartoon might run on a leaf “volume” node, and require 1 “volume_lock”, 1 “disk_io” on its parent host node, and 2 “Gbps” on the grand-parent rack switch node.

Each Bistro scheduler also automatically creates a special node called the instance, which is usually used at the common ancestor for all other nodes, and is used to implement global (per-scheduler) concurrency limits.

Node Sources

Bistro loads the resource tree via “node sources”. These are executed periodically, which allows Bistro to dynamically update its list of nodes as the underlying data changes. Node fetchers are written as “plugins” so that it’s fairly easy to add more for different types of data.

Task Status

Each task has a status. Bistro remembers the last status of each task. This prevents it from rerunning tasks that have already finished, and is useful for monitoring. The common statuses are:

running: The task is currently running.done: This task has finished. Bistro won’t run it ever again.incomplete: This task ran at least once and wants to run again, but it hasn’t been scheduled yet.error_backoff: This task failed on its previous run, and is currently waiting for its back-off period to expire before trying again.failed: This task failed permanently and Bistro should not try to run it again.

Note: the REST API has a forgive_jobs handler, which will immediately release any tasks from back-off, and will also allow permanently failed tasks to retry. This is useful if you are rolling out a fix that caused your task to crash on a portion of the data. See HTTPMonitor.cpp) for handler usage.

Shell-command can write their status to their argv[2] as one of the above strings, or as a JSON string with extra metadata (see Task execution). A task that fails to emit a status is taken to be in “error_backoff”, unless it was killed by Bistro. In rare cases, you might use other status codes not listed above.

Depending on its settings, the scheduler may persist the status only in memory, or in some kind of database (e.g. local SQLite). In either case, if the worker host or scheduler host goes down at an inopportune time, it is entirely possible for a status to be lost between the time that your task writes it, and when the scheduler records it. Therefore, please do not treat statuses as reliable checkpoints. However, for idempotent tasks, you can use statuses to pass small amounts of state from one invocation of your task to the next.

Execution Control

In Hadoop, your entire job starts, runs, and either succeeds or fails. In contrast, Bistro continuously reports the status of every task that that could possibly run against the currently defined nodes. It is up to you to define success or failure criteria for your entire job — this is essential for coping with large-scale distributed-computing contexts, in which nodes may come and go at any time, and in which some failure must be tolerated.

Furthermore, in Bistro, you can:

- control task back-off policies globally (in

bistro_settings) and per-job - change job settings (and available nodes) while the job runs, but changes will not affect task instances that are done or already running

- pause or resume jobs by changing their

enabledflag — watch out, existing tasks will may get killed, depending on the value ofkill_orphan_tasks_after_sec

Bistro also provides a wide range of filters (specified per level) so you can run tasks against only a subset of nodes.

Search the Configuration guide to learn more about the settings mentioned above.

Scheduler Policy

A Bistro scheduler can run multiple jobs in parallel. Coming back to the database migration example, if you have 7 jobs running concurrently on 100k DB shards, Bistro will start as many of the 700k tasks as it can without exceeding resource limits.

Bistro schedules via one of several greedy heuristics — it does not optimize make-span or try to solve NP-complete problems. It aims for high throughput on small, interchangeable tasks at the expense of creating optimal schedules for highly constrained tasks & resources. It can still be useful in the latter kind of setting, but expect to have less efficient or performant scheduling, or to write your own custom heuristic scheduling policy.

Out of the box, Bistro comes with the following scheduling policies, which can be used to make a few kinds of trade-offs between different kinds of task fairness, or prompt job completion:

-

Round Robin. Randomly shuffle the jobs, and start one eligible task for each job, in the selected order. This is the default, and is useful if you have many different users adding jobs and don’t want one job to slow down the rest.

-

Randomized Priority. This is like round robin, except that instead of treating each job equally, we bias in favor of jobs with higher priority. The probability of selecting a task from a given job at each iteration is (job priority)/(sum of all priorities).

-

Ranked Priority. In this mode we treat the priority as a rank, and select all eligible tasks from the highest priority job, followed by tasks from the second highest priority job, and so on.

-

Long Tail. In this mode we rank by number of remaining tasks, preferring jobs with the fewest tasks remaining. This can be a risky setting because one job that fails repeatedly on a node can hold off other jobs from running on that node.

Runners: Executing work locally or remotely

Bistro executes tasks using a Runner plug-in. It ships with two implementations:

LocalRunner

This worker starts the task as a subprocess of the scheduler — i.e. the scheduler and the task co-locate on the same host.

We use this type of worker to place tasks on data hosts directly, avoiding network data transfer. By starting a scheduler-per-host, you avoid having a single point of failure. For monitoring such deployments, the UI is capable of aggregating job status across thousands of schedulers. To use this mode, pass --worker_command to bistro_scheduler.

RemoteWorkerRunner

The scheduler dispatches tasks to a pool of hosts running a bistro_worker process.

We support worker resource constraints so you can control how tasks are allocated to worker hosts. This lets us run fewer heavy-weight tasks per worker host, or to schedule more work on bigger hosts — see Nodes and Resources for many more details.

By default, Bistro will assign tasks to workers in a round-robin fashion, subject to worker resource availability. This can be changed by setting bistro_settings → remote_worker_selector to one of these values:

-

busiest: For the task to be scheduled, iterate through the workers in increasing order of their “remaining capacity”, defined as

sum(r.weight * r.slots_remaining for r in worker.resources), whereweightcomes frombistro_settings → resources → LEVEL -> RESOURCE -> weightandslots_remaining, andslots_remainingis that specific worker’s capacity in that resource, minus the slots used by the tasks already running on the worker.

Then, pick the first worker that can fit the task.

-

roundrobin: Advances a pointer in a non-deterministic order to loop over the set of workers, so that

number of workersscheduling attempts elapse before we reuse any given worker.

Bistro uses a high-throughput distributed consensus protocol, which is designed for rapidly starting many tasks with minimal round-trips, while guaranteeing that a task instance will be started at most once in real-world scenarios (the protocol is not byzantine fault-tolerant). While Bistro ships with reasonable defaults, the configuration and tuning of this protocol is tricky and will require you to familiarize yourself with the design documents, and in-code documentation:

- Overall design

- RPC documentation

- What is initial wait, and how long is it?

- For command-line flags, see

DEFINE_directives in RemoteWorker.cpp, RemoteWorkerState.cpp, and RemoteWorkers.cpp.

You will likely want to ask for help with these settings. When doing so, please describe very precisely what trade-offs you would like to make concerning:

- Task durability — how long can the scheduler be down before running tasks start to be killed?

- Worker fail-over latency — if a worker fails, how long must a replacement worker wait before it can start the old worker’s tasks?

- Scheduler restart latency — in the worst case, if the scheduler goes down for a while, and some workers fail concurrently, how long can a scheduler take to come back up?